Los Angeles American Indian and Alaska Native Project

[1]

Technical Memo 3:

Working but Struggling

Jonathan Ong and Paul Ong

June 3, 2012

Revised July 25, 2013

Introduction

This technical memo examines

labor-market outcomes for American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs),

particularly compared to non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) in Los Angeles County. The

analysis uses data from the 2007-11 American Community Survey (ACS).

Descriptions of this data source can be found in previous technical memos. When

possible, the project utilizes tabulations published online by the Bureau of

the Census (http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml).

That information is based on the full sample of respondents, which covers more

than 12% of the population. The project also uses the 2007–2011 ACS public-use

micro sample (PUMS), which contains individual level information for about 5%

of the population. PUMS allows the project to customize the analysis to examine

issues not adequately addressed by or reported in published statistics.

The rest of the memo is organized in

four sections. The first provides an overview of the labor-market status of

AIANs and other major groups. The second section compares annual earnings, both

the averages and relative proportions at the bottom of the economic ladder. The

third section analyzes the earnings gap between US-born non-Hispanic Whites and

AIANs, and whether a gap between the two groups in income remains after

accounting for human capital. The last section examines the paradoxical role of

low educational attainment and high returns to schooling for AIANs.

The empirical findings show that AIANs

are active in the labor market, but a disproportionately high number are

struggling. They have a harder time finding work, earn less, and are more

concentrated in the low-income sector. The results indicate that the economic

disadvantages are due both to less education and labor-market barriers such as discrimination.

On the other hand, the analysis reveals that AIANS experience considerable

economic benefits from higher educational attainment.

Part

I: Overview of Labor Market Status

Table 1 summarizes the available

information on the labor-market status of the 16 years and older population.

Statistics are based on the categories used by the Bureau of the Census and reported

for the major racial/ethnic groups and by sex. The figures for AIANs, Asians,

and African Americans (aka "Blacks") are based on the single race category

(that is, the numbers do not include those who are multiracial), and the

Hispanic category includes all Hispanics (aka "Latinos") regardless of race.

The NHW category includes those who are white alone and not of Hispanic

origins. The analysis in this section uses three common indicators: the

labor-force participation rate, the unemployment rate, and the

full-time/full-year rate. The definitions are given below.

As with other studies of the economic

effects of race, the NHW population is taken as the reference group because

members of this population face fewer labor-market barriers than minority

workers. Moreover, using this benchmark is desirable because NHWs and AIANs are

predominantly US-born; thus they should be more comparable in the absence of

barriers confronting AIANs. Being US-born, however, does not ensure equal

outcomes, and this is apparent for African Americans. They have the same

nativity characteristics as NH whites (mostly US-born), but Blacks have been

extremely disadvantaged by past and current discrimination and

institutionalized racism. Comparisons with Asians and Hispanics should be

viewed cautiously because both groups are predominantly foreign-born. Their

labor-market characteristics

and dynamics are complicated by American

immigration policies and practices that produce selective migration patterns.

The net results are a very highly educated Asian labor force and a far less

educated Latino labor force. Moreover, linguistic and cultural factors affect

the dynamics of economic incorporation and assimilation of foreign-born workers.

The analysis examines outcomes by sex

because males and females have different relationships with paid work. Female

participation tends to be lower and less continuous than male participation because

a division of tasks still exists within a family or household. Women take on more

of home duties such as childrearing, cleaning, and shopping. Females also

encounter employment discrimination, which can have a noticeable effect on

labor-market outcomes. The gender bias in the social division of household

duties and overt sexism has waned, but neither has disappeared.

The broadest measure of the level of

labor-market activity is the labor-force participation rate (LFPR), which is

defined as the proportion of the 16 and older population that is either

employed or actively seeking employment. This economically engaged segment of

the population is categorized as being "in the labor force," and the analysis

focuses on the civilian sector (that is, excluding those in the armed forces

when possible). AIAN LRPFs are roughly comparable to those for the total

population and for NHWs, and this holds regardless of sex. (Not surprisingly,

the LFPRs for females are consistently lower than for males.) In other words,

the data show that AIANs are economically active.

Table 1: Labor Market Status

|

||||||

Total

|

NHWs

|

Asians

|

Blacks

|

AIANs

|

Hispanics

|

|

Both Sexes, 16 & older

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Labor Force Participation

|

65.1%

|

64.5%

|

62.9%

|

60.7%

|

64.7%

|

67.2%

|

Unemployment Rate

|

9.8%

|

8.3%

|

7.5%

|

14.6%

|

12.0%

|

10.6%

|

FTFY Rate

|

61.2%

|

59.1%

|

64.9%

|

60.3%

|

58.6%

|

61.9%

|

Male

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Labor Force Participation

|

72.6%

|

71.3%

|

68.7%

|

61.7%

|

71.0%

|

77.0%

|

Unemployment Rate

|

9.8%

|

8.8%

|

8.0%

|

16.1%

|

11.2%

|

10.0%

|

FTFY Rate

|

66.1%

|

64.6%

|

69.0%

|

61.0%

|

63.7%

|

67.3%

|

Female

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Labor Force Participation

|

58.0%

|

57.7%

|

58.0%

|

59.8%

|

58.2%

|

57.6%

|

Unemployment Rate

|

9.8%

|

7.8%

|

7.2%

|

13.1%

|

12.8%

|

11.5%

|

FTFY Rate

|

55.4%

|

52.5%

|

60.8%

|

59.7%

|

51.9%

|

54.7%

|

FTFY refers to full-time, full-year work. Source: 2007–2011 ACS. |

||||||

Despite being active in the labor

market, AIANs have a harder time finding work. This can be seen in the

unemployment rate (UR), which is the percent of the civilian labor force that

does not have a job (which is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed

by the sum of the employed and unemployed). Nearly one in eight AIANs in the

labor market is without a job, nearly one and a half times as prevalent as for

NH whites. This disparity holds for both male and female AIANs. Moreover, the

AIAN URs are higher than those for the total labor force, Asians, and

Hispanics. Only Blacks have a higher unemployment rate. The statistics clearly

show that AIANs are among the most disadvantaged in terms of encountering

difficulties in finding work.

Along with higher unemployment rates,

AIANs are less likely to work full time and full year (FTFY), which is defined

as having worked at least 50 weeks in the previous year, averaging at least 35

hours per week. The FTFY rate is the FTFY workers as a percent of all who

worked in the previous year. The AIAN LFPR is over three percentage points

lower than the population (16 and older). In fact, the AIAN rate is lower than

those for all other racial/ethnic groups. The gap is much larger among females.

Part

II: Annual Earnings

AIANs are also disadvantaged in terms of

annual earnings. Table 2 reports median annual earnings. The median is the

amount that divides the working population so half earn more and half earn

less. Earnings include both paid employment and income from self-employment,

and the amounts are reported in 2011 dollars. The medians for both sexes

combined (top third of the table) are estimated by the authors from categorical

data. The typical (median) AIAN worker earned 58¢ for every dollar earned by the

typical NHW worker, an amazing large disparity. The typical AIAN also earned

less than the total working population, Asians, and African Americans. The

disparity is slightly lower among FTFY workers but still substantial, with

AIANs earning 60¢ for every dollar earned by the typical NHW worker, but the

AIAN-NHW gap is larger among those working less than FTFY.

Table 2: Median Earnings in the Past 12 Months

|

||||||

Total

|

NH Whites

|

Asians

|

Blacks

|

AIANs

|

Hispanics

|

|

Both Sexes

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

$29,348

|

$44,446

|

$36,100

|

$31,714

|

$25,797

|

$21,510

|

FTFY

|

$41,334

|

$63,157

|

$48,052

|

$44,190

|

$38,000

|

$29,255

|

Not FTFY

|

$12,758

|

$17,242

|

$13,918

|

$12,085

|

$11,192

|

$11,145

|

Male

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

$31,972

|

$52,719

|

$39,795

|

$32,459

|

$27,446

|

$23,892

|

FTFY

|

$42,377

|

$71,638

|

$50,800

|

$45,389

|

$39,180

|

$30,024

|

Not FTFY

|

$14,218

|

$20,086

|

$14,973

|

$12,479

|

$11,735

|

$12,489

|

Female

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

$25,920

|

$36,601

|

$32,387

|

$31,064

|

$22,343

|

$18,674

|

FTFY

|

$39,399

|

$54,029

|

$44,989

|

$42,975

|

$36,321

|

$27,381

|

Not FTFY

|

$11,749

|

$15,626

|

$13,077

|

$11,738

|

$10,641

|

$9,984

|

| Source: 2007–2011 ACS. | ||||||

The AIAN-NHW gap is larger among males

(the relative difference in the median for NHW males and AIAN males) than among

females (the relative difference in the median for NHW females and AIAN

females). The latter phenomenon (smaller gap among females) is due in part to

the fact that NHW females earn considerably less than their male counterparts

(NHW males). Nonetheless, the data indicate that AIAN females earn less because

of their race and gender.

As a consequence of earning less, AIANs

are more concentrated in the lower economic rungs, which can be seen in Table

3. The top half of the table reports the percent of each group falling into two

low-income categories, those earning less than $10,000 and those earning

between $10,000 and $19,999. Among all workers (both FTFY and non-FTFY), AIANs

have the highest odds of being in the lowest category, with nearly one in five

earning less than $10,000. AIANs are also more likely to be in the next income

category relative to all workers, NH whites, Asians, and African Americans. In

other words, AIANs are disproportionately more likely to be low-income workers,

to be among the "working poor."

An alternative measure of the economic

status of workers is the economic well-being of their families. Data on

individual earners do not capture the complexity of families. The same income

has very different consequences on the quality of life for a small family than

for a large family. The alternative approach is to classify workers according

to the federal poverty line (FPL), which is based on approximately three times

the cost of the typical food basket for a family according to size. For the 48

states on the mainland, the 2001 FPL ranges from $11,484 for a single person to

$23,021 for a family of four and to $39,069 for a family of eight. There are

slight adjustments to the FPL depending on whether the head is elderly or not

and on the ratio adults to children.

Table 3: Employed by Earnings and Poverty Categories |

|||||||

Total

|

NHWs

|

Asians

|

Blacks

|

AIANs

|

Hispanics

|

||

By Annual Earnings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All Employed

|

|

|

|

||||

$9,999 or Less

|

17.1%

|

15.0%

|

14.9%

|

18.3%

|

20.2%

|

18.9%

|

|

$10,000 to $19,999

|

18.8%

|

10.8%

|

13.6%

|

14.6%

|

19.8%

|

27.2%

|

|

FTFY Employed

|

|

|

|

||||

$9,999 or Less

|

2.2%

|

1.5%

|

1.8%

|

1.9%

|

3.5%

|

2.8%

|

|

$10,000 to $19,999

|

15.2%

|

5.1%

|

9.1%

|

9.5%

|

13.6%

|

25.5%

|

|

By Poverty Status

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All Employed

|

|

|

|

||||

Less Than 1.5x FPL

|

16.9%

|

8.4%

|

11.0%

|

16.7%

|

19.3%

|

25.1%

|

|

1.5-2.49x FPL

|

18.2%

|

9.3%

|

14.2%

|

16.7%

|

22.0%

|

26.3%

|

|

FTFY Employed

|

|

|

|

||||

Less Than 1.5x FPL

|

11.4%

|

3.1%

|

5.6%

|

7.7%

|

9.3%

|

20.1%

|

|

1.5-2.49x FPL

|

17.4%

|

7.1%

|

12.8%

|

15.2%

|

20.0%

|

26.7%

|

|

| Source: Annual Earnings Statistics from published 2007–2011 ACS information, workers by poverty status based on tabulations of 2007–2011 ACS PUMS data by authors. | |||||||

One of the limitations of the FPL is

that thresholds are not adjusted for geographic location despite the fact that the

cost of living in large urban areas, such as Los Angeles, is considerably

higher than in other regions. For this reason, the project classifies families

with less than one and a half times the FPL as being poor. Families in the

range of 1.5 times and 2.49 times the FPL are classified as being lower-income.

The percentages in the second half of table 3 are based on these definitions,

and the statistics are based on tabulations of PUMS data by the authors.

The empirical results show that nearly

one in five AIAN workers lives in a poor family, a proportion higher than all

other groups except Hispanics. Another one in five AIAN workers lives in a lower-income

family, again a rate higher than all other groups except Hispanics. In other

words, AIANs are disproportionately over-concentrated among the poor and those

with limited income. Working FTFY lowers the percentages, but does not change

the relative positions of racial/ethnic groups. AIAN FTFY workers are more

likely to be at the bottom end of the economic ladder relative to NH whites,

Asians, and Blacks.

The findings in this section show that

too many AIANs are financially struggling, working but unable to earn enough to

lift their families into the middle class. Although the consequences of lower

earnings are obvious, the causes are more difficult to determine.

Part

III: The AIAN-NHW Earnings Gap

This section of the technical memo

provides additional insights into the earnings gap between AIAN and NHW workers

reported earlier. While the observed disparity is sizable, it could be due to a

number of factors. The main objective of the analysis is to test whether being

AIAN has an adverse effect on outcomes after accounting for economic factors

that normally determine earnings. According to mainstream labor economics and

assuming a competitive labor market, human capital is the key to productivity

and compensation to labor. Human capital comes in two forms, through formal

schooling (education) and from on-the-job training (OJT, both general and firm-specific).

Markets, however, may not be perfectly competitive. For example, minorities and

women may be treated less favorably than NH white males in terms of

recruitment, screening, hiring, access to OJT, retention, and promotion. These

practices are usually seen as discrimination, which can be either overt or

subtle. The latter form is associated with unconscious prejudices, prevailing

stereotypes (which can have a statistical foundation but are generalized to all

members of a group, a phenomenon known as statistical discrimination), and

differential access to social networks. Labor markets also are also affected by

the business cycle, so outcomes vary from year to year.

The analytical challenge is to

empirically isolate the contributions of human-capital factors from other

factors. The analysis uses the following modified multivariate human-capital

model to conduct the analysis, and the model’s specification is based on the

available data, which is discussed later.

Ej =

α + β(Edj )

+ γ(Expj ) + λ(Yrj) + φ(Gj)

+σj , for workers j=1...m

Ej is the dependent (outcome) variable defined as the log of annual earnings for

worker "j". The other variables are the independent (or causal) variables,

which are hypothesized to influence the level of earnings

Edj is the number of years of schooling

Expj is the potential number of years of work experience

Yrj is a vector of dummy variables denoting the year of the survey

Gj is a vector of dummy variables denoting race-sex groups other than NH white

The

following are parameters that are statistically estimated:

α is

a constant (intersect)

β and

γ are coefficients relating schooling and experience to Ej

λ and

φ are vectors of coefficients relating years and groups to Ej

Finally, σj is the random error for observation "j", the unexplained variance not captured by the included independent variables. This model assumes that the economic returns to education and experience are the same for all groups. This assumption is relaxed in the subsequent section of the technical memo.

The data come from the 2007–2011 PUMS.

Schooling is based on the highest year of education completed. Other variables

are calculated from available information. For example, there is no reported

data on years worked; therefore, the value for the potential years of work

experience is calculated as age minus the years of schooling minus 5 years. The

empirical model also uses the square value of the potential years of experience

because the economic return to OJT declines with fewer years of work before

retirement. The vector of years is included because the ACS data are based on

responses over five years, thus labor-market outcomes were affected as the

economy entered into the "great recession." (See previous technical memo for

details on the business cycle.) The vector of groups includes NHW females, AIAN

males, and AIAN females. The excluded (reference) group is NHW males.

The subsample from PUMS includes AIAN

and NHW workers with reported earnings in the previous year who are at least 16

years old, US-born, and not currently enrolled in school. Immigrants are not

included to simplify the analysis because modeling the process of economic

assimilation is complex and beyond the scope of the project. Moreover, the

sample of AIAN immigrants is too small for any detailed analysis.

Weighted ordinary least-square regressions are used to

estimate the coefficients (α, β, γ, λ and φ) for the independent variables. The weight is the

probability of being included in the survey. A coefficient is interpreted as

the impact of increasing the value of the associated independent variable on

earnings. For example, one more year of schooling (ΔEd=1) would increase

earnings by a factor related to β. Most studies show that getting one additional year

of education increases annual earning by more than a tenth. The primary

independent variables of interest are those for groups other than being NHW

male, the reference category. If an observed inter-group difference (e.g., the

earnings gap between NHW males and AIAN males) is due just to variations in

years of schooling and experience, then the estimated value of φ should be

statistically no different than zero. This would imply that there is no

additional burden or economic cost of being AIAN in the labor market other than

the influence of differences in human capital. However, if φ is negative

and statistically significant, then the finding means that the earnings gap

between the two groups cannot be explained away because of differences in

education and experience.

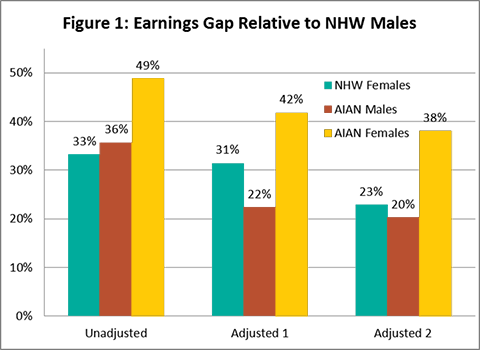

Figure 1

summarizes the key regression results, all of which are statistically

significant. The height of the bars represents the estimated earnings gap

between a group (NHW females, AIAN males, or AIAN females), and NHW males. The

first series (leftmost three bars) reports the unadjusted gaps, that is, the

differences controlling only for the year of survey but not controlling for

schooling and experience. (The estimated gaps are different than those reported

in Part II because of differences in the included populations and methodologies

to calculate the disparities.) The gaps are sizable, particularly for AIAN

females. The second set of bars (middle three) reports the gaps after

accounting for human capital factors and year of survey. The gaps do decrease,

indicating that some of the earnings gap is due to variations in education and

experience. For example, the disparity between AIAN males and NHW males drops

by more than a third. Nonetheless, there are still sizable residual differences,

indicating that nonhuman capital factors contribute significantly to disadvantaging

the three groups. AIAN males earned about 22% less, and AIAN females earned 42%

less. The final set of bars (rightmost) contains the results for an alternative

model that includes being FTFY as an additional control (independent) variable.

This modification lowers the gaps but only marginally for AIAN males and AIAN

females. Rerunning separate regressions for males and females produces similar

results in terms of the NHW-AIAN gap within each group by sex.

Estimates

by authors based on analysis of 2007–2011 ACS PUMA.

The sizable estimated impact of just

being AIAN on earnings, after accounting for human capital, indicates that AIAN

workers face enormous difficulties in making a decent income. This is commonly

interpreted as the unexplained or unjustified economic cost of being AIAN in

the labor market. As mentioned earlier, poor labor-market outcome could be

partially due to employment discrimination. The gap may also be due to

unobserved differences in the quality of schooling; that is, AIANs may have had

an inferior education for any given level of attainment relative to NHW males.

This type of inequality can be considered to be a form of pre-labor-market

discrimination or institutionalized racism. Unfortunately, ACS does not collect

information on employment discrimination or the quality of education. Despite

this data limitation, the findings nonetheless reveal that AIANs are

encountering formable hurdles that contribute to lower income for AIAN workers

and the disproportionate concentration of AIANs among the working poor.

Part

IV: Education

Improving education opportunities is one

potential strategy to improving the labor-market outcome for AIANs. AIANs have

lower educational attainment than NH whites, which is detailed below.

Simulations based on the estimated econometric model in the previous section

indicate that closing the education gap between NH whites and AIANs would cut

the earnings gap in half. While increasing schooling for AIANs is not a panacea

because there are still other employment barriers, promoting education could

nonetheless greatly improve the economic well-being of AIANs and their

families.

Table 4: Educational Attainment, 25 and

Older

|

||||||

Total

|

NH Whites

|

Asians

|

Blacks

|

AIANs

|

Hispanics

|

|

All

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Less than High School

|

23.9%

|

6.7%

|

13.1%

|

12.6%

|

28.9%

|

45.0%

|

High School or GED

|

20.8%

|

18.2%

|

15.1%

|

24.6%

|

23.5%

|

24.4%

|

Some College or AA

|

26.0%

|

30.1%

|

22.6%

|

39.9%

|

32.2%

|

20.6%

|

BA/BS Plus

|

29.2%

|

45.0%

|

49.2%

|

22.8%

|

15.4%

|

10.0%

|

Male

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Less than High School

|

23.8%

|

6.4%

|

10.8%

|

13.8%

|

29.2%

|

45.4%

|

High School or GED

|

21.0%

|

17.1%

|

14.5%

|

26.9%

|

23.7%

|

25.4%

|

Some College or AA

|

25.2%

|

28.9%

|

23.6%

|

37.3%

|

31.2%

|

19.9%

|

BA/BS Plus

|

29.9%

|

47.6%

|

51.1%

|

22.0%

|

16.0%

|

9.3%

|

Female:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Less than High School

|

24.0%

|

7.0%

|

15.0%

|

11.7%

|

28.7%

|

44.7%

|

High School or GED

|

20.7%

|

19.3%

|

15.6%

|

22.7%

|

23.2%

|

23.4%

|

Some College or AA

|

26.9%

|

31.4%

|

21.8%

|

42.1%

|

33.2%

|

21.3%

|

BA/BS Plus

|

28.5%

|

42.4%

|

47.7%

|

23.4%

|

14.9%

|

10.6%

|

| Source: 2007–2011 ACS. | ||||||

The statistics in table 4 show the

degree of disparity in educational attainment among the major racial/ethnic

groups. The figures are based on the adult population that is at least 25 years

old, including those in and outside the labor force. Hispanics have the lowest

educational attainment because of the large number of Latino immigrants who

received very limited schooling prior to entering the United States. AIANs are

more concentrated at the bottom end (those who did not complete high school)

and less likely to have a four-year college degree than the total population,

NH Whites, Asians, and Blacks. This educational disparity holds for both males

and females. Compared with NH Whites, AIANs are about four times as likely to

not have a high school degree (or its equivalent such as a GED), and only a

third as likely to have a bachelor’s degree.

Although AIANs with the same level of

education earn less than their NHW counterparts, important questions are whether

there are economic benefits to schooling among AIANs and, if so, how much. More

specifically, what is the increase in earnings from an additional year of

education for AIANs, or worded slightly differently, what is the difference in

earnings between AIANs with more education compared to those with less education?

The human-capital regression model used in the previous section assumes that

the rate of return to education is identical for everyone in the sample. More

specifically and on the average, there is, on the average, an estimated 12%

increase in earnings for every additional year of schooling. This assumption of

equal rates of return can be relaxed by estimating separate regression models

for each of the four race-sex groups (NHW males, NHW females, AIAN males, and

AIAN females), thus generating separate estimated rates of return.

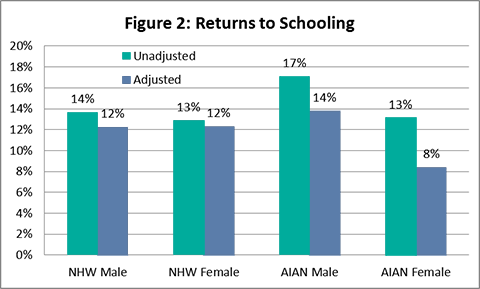

Figure 2 reports the key results from

the race/sex-specific empirical models. The gray bars report the estimated

rates of return to schooling after accounting for the year of the survey. The reported

percentages are the estimated increases in earnings from one more year of

education, and they indicate that the rates for AIANs are at least as large as

those for NH whites. The black bars report the estimated returns from models

that account for experience, survey year, and being FTFY. These additional

controls lower the estimated effects of education, but there are still

substantial benefits from schooling, particularly for AIAN males. The

noticeable drop for AIAN females is due to a strong correlation between

educational attainment and the odds of working full-time and full-year. Adjusting

for that association generates an approximate 12% rate for return for AIAN

females.

Improving educational attainment is not

sufficient to eliminating the poor labor-market outcomes for AIANs, but it is

probably a necessary element of a multi-pronged strategy. Moreover, addressing

the problem through the lens of schools enable AIANs to tackle an issue through

public policy since education is a public good. Moreover, there is broad

support for the proposition that all children should have a decent education.

Conclusion

and Recommendations:

This technical memo reports the results

from an analysis of 2007–2011 ACS data to document the labor-market status and

outcomes for American Indians and Alaska Natives in Los Angeles. The project

examines standard economic indicators and utilizes statistical techniques to

generate additional insights. The major findings are:

1.

AIANs are economically active in the labor market;

2.

AIANs have more difficulties finding jobs and working

full-time/full-year;

3.

AIANs suffer from an earning gap relative to NH Whites;

4.

Lower earnings push a disproportionate number of AIANs

into the working-poor class;

5.

Differences in the stock of human capital explain some

of the NHW-AIAN earnings gap;

6.

There is a sizable "cost of being AIAN" beyond

differences in human capital; and

7.

Closing the educational gap can ameliorate negative

labor-market outcomes.

The analytical findings point to the

following recommendations:

1.

Additional research to identify the exact nature of

the labor-market barriers facing AIANs;

2.

Greater enforcement of antidiscrimination laws to

protect AIAN workers; and

3.

Increase educational attainment opportunities for AIANs.

We would like to thank our sponsors, The California Wellness Foundation, Los Angeles County Board of Supervisor Don Knabe, and the UCLA Center for the Study of Inequality for their generous support. We would also like to thank the authors, Paul Ong and Jonathan Ong, as well as the American Indian Studies Center for supporting this project. |

[1] This technical memo is a product of a collaborative effort by UCLA American Indian Studies Center and the Los Angeles Urban Indian Roundtable. We would like to thank reviewers for their input, feedback, and comments. The authors are solely responsible for the contents of this report.