Los Angeles Urban Indian Roundtable

![]() Published by the UCLA American Indian Studies Center

Published by the UCLA American Indian Studies Center

Access to Care Among American Indians and Alaska Natives in Los Angeles

Policy Brief Number Four, February 2016

Introduction

Los Angeles continues to be one of the largest and most diverse metropolitan areas in the country. Correspondingly, Los Angeles is also home to the nation's largest population of American Indians and Alaska Natives (roughly 222,000 according to a US Census Bureau report released in June 2015).1 A little known fact is that nearly 70% of the nation's 5.2 million American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN) live in urban areas.2 Sometimes referred to as "Invisible Tribes," these urban-dwelling AIANs face unique and complex challenges when trying to access health care. This policy brief describes the current landscape of health care coverage for AIANs residing in Los Angeles. It highlights some of the misperceptions about access in this special population; identifies their current barriers to care; and formulates recommendations to optimize the health and well-being of this vulnerable yet resilient population.

Assumption #1: All American Indians and Alaska Natives, including those residing in Los Angeles, are eligible for free health care through the Indian Health Service (IHS).

FALSE. In exchange for land and natural resources, the US government is legally obligated to provide health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives. This obligation is codified in legislation, treaties, and intergovernmental policies over centuries, and is also part of the Federal Trust Responsibility.3 However, IHS is not a health insurance program, and does not provide minimum essential health benefits.

Numerous federal policies have interfered with this health care obligation. First, Termination Era policies resulted in countless tribes being stripped of their sovereignty, land base, and federal recognition, making the perception of eligibility for IHS services of non-federally recognized tribes complicated. In reality, there is no tribal or ethnic requirements to use urban Indian clinics, but this may vary for tribal clinics. For instance, of those AIANs in California who identify as being from a California tribe, only 45% reported having access to IHS services.4 This may be due to the fact that many California tribes continue legal battles to gain or regain recognition by the federal government.5 Tribes indigenous to Los Angeles County do not have a land base, or federal recognition, and there is no specific data on their access to care.

Second, the Relocation Era resulted in a large demographic shift of AIANs from their tribal lands to urban areas. If one does not live on or near the reservation of the tribe in which the individual is enrolled, it may be difficult to access certain services out of that service delivery area. This is true of of AIANs residing in California who are not from a California tribe; only 9% reported having access to IHS. AIANs from non-California tribes represent 50.9% of all AIANs in California.6

Third, the IHS budget is only funded at 56% of need, with the lowest per capita spending compared to all other Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) agencies.7 Despite the fact that more than 70% of AIANs reside in urban areas, only 1% of the total IHS budget is allocated for Urban Indian Health Organizations.8 Even if urban AIANs do have access to IHS, often the services are limited to primary care. Hence, urban AIANs cannot solely rely on the IHS as a usual source of care, or for specialty care. This point is particularly salient in Los Angeles, where there is currently only one Urban Indian Health Organization for the entire county.

Assumption #2: Since a large proportion of AIANs live at or below the federal poverty level (FPL), the level of uninsured should be low due to coverage by public insurance programs such as Medi-Cal, Medicare, or the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).

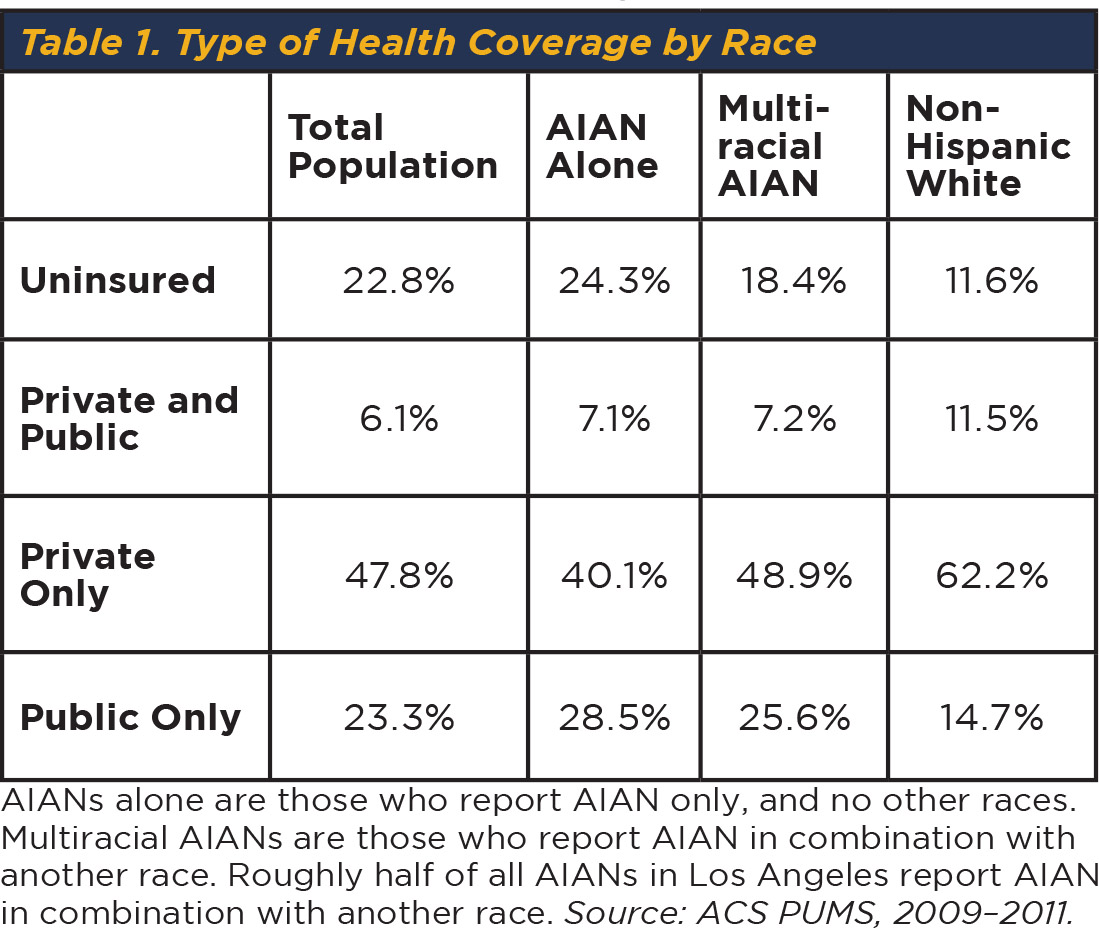

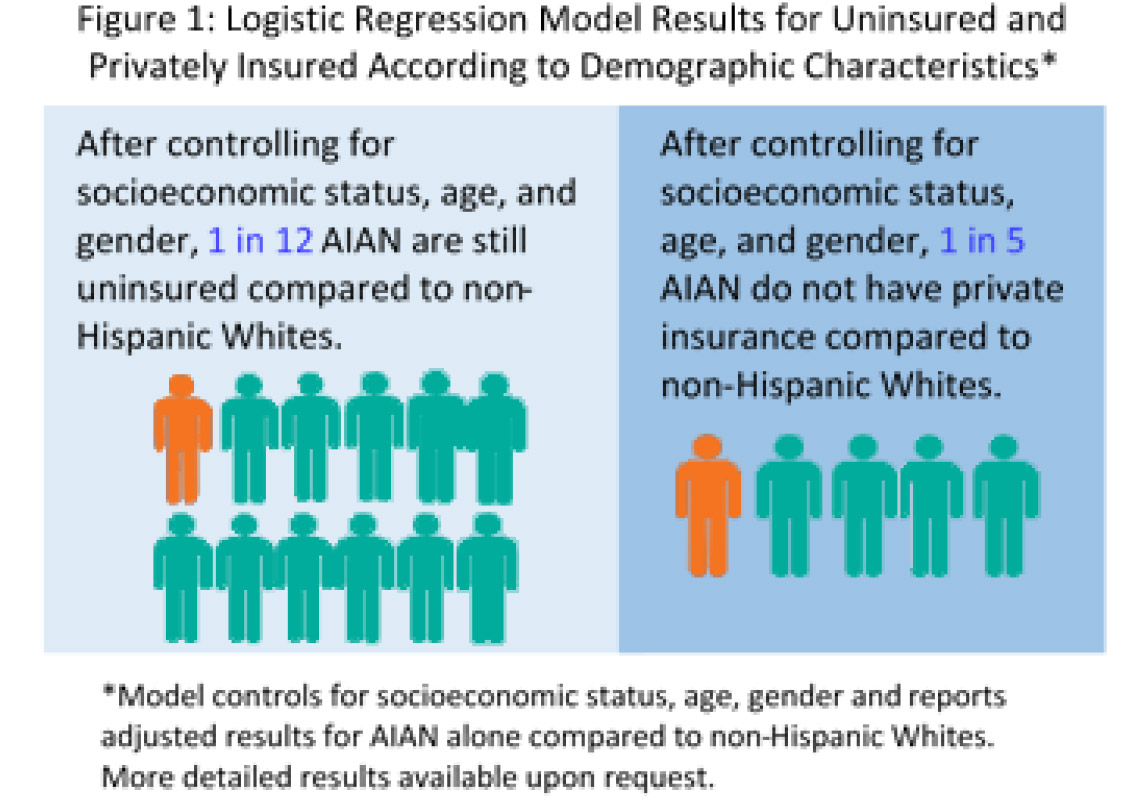

FALSE. Nearly one-fifth of AIANs in Los Angeles are uninsured, despite their overrepresentation in public insurance programs compared to non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) (table 1). Overrepresentation in public insurance programs is in part explained by high unemployment and poverty rates.9 AIANs who are between the ages of 18–64, male, greater than 125% of the FPL, and with a disability are more likely to be uninsured (appendix, table 2).* Even after controlling for these factors simultaneously in a statistical model, AIANs are still more likely to be uninsured and without private insurance compared to NHWs (fig. 1).* One potential reason for this is historical mistrust. AIANs, as well as other communities of color, have reasons to distrust government programs, researchers, and clinicians due to past experiences including involuntary sterilization, mishandling of research specimens, and withholding of information.10,11 Cultural barriers such as language differences between provider and patient, fear, intimidation, and preference of traditional beliefs may also contribute to disinterest in seeking out Western medicine.12,13

Assumption #3: With the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), and the reauthorization of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (IHCIA), AIANs are receiving better access to health care.

Unfortunately, there is limited data on AIAN access to care after the passage of the ACA. Between October 2013 and April 2014, roughly 4,000 AIANs in California enrolled in a subsidized insurance plan (excluding Medi-Cal).14 Under the ACA, every American is guaranteed subsidies for health insurance if they fall within certain income levels.

In addition, federally recognized AIANs are eligible for special provisions:15

- AIANs do not have to wait for special enrollment periods. They can enroll in an insurance plan at virtually any time.

- AIANs with a family of four who earn less than 300% of the FPL do not have to pay certain out-of-pocket expenses, such as copays or deductibles, if they enroll through Covered California.

- There is no cost sharing for covered services provided by an AIAN health provider or clinic, regardless of income.

- AIANs are exempt from the individual mandate and the associated penalty if they fail to maintain minimum essential coverage.

While these special provisions take into consideration the federal Indian trust responsibility, there are unintended consequences associated with them. For example, these provisions are limited to those AIANs enrolled in federally recognized tribes (or who otherwise qualify for IHS). Exemption from the penalty of the individual mandate may have the unintended consequence of disincentivizing AIAN individuals from enrolling in an insurance plan at all. Further, enrollment in IHS alone does not meet the minimum essential coverage requirement.16

Recommendations to Improve Access to Health Care for American Indians and Alaska Natives Who Reside in Los Angeles County:

Data

- Disaggregated data on AIAN tribal affiliation is critical and has important implications on access to resources.

- Garnering resources to conduct a periodic independent health assessment of AIANs using culturally congruent methods and sampling, with additional triangulation of multiple data sources and with oversight from a community advisory board, would be useful for tracking the needs of this vulnerable population.

Best Practices in a Culturally Sensitive Medical Home

- Given excess morbidity and mortality, higher burdens of psychiatric and substance abuse diagnoses, and historical trauma, access to a culturally sensitive medical home is a best practice in promoting health equity among AIANs. For example, while Los Angeles has the highest number of AIANs in the nation, there is only one Urban Indian Health Organization in the county that meets this definition.

- Current literature details how community-informed and traditional practices can be complementary to conventional therapies in addressing mental health and substance abuse disparities, particularly here in Los Angeles.17,18,19 Consideration should be given to how these complementary practices can be made available to the community (e.g., expansion, reimbursement, etc.).

- Creating partnerships between local AIAN organizations, county stakeholders, local government, private interests, and academic institutions can help:

- increase the AIAN health professional workforce by building pipeline training programs in Los Angeles;

- increase AIAN access to quality health professionals, and increase non-AIAN cultural sensitivity by having the only AIAN clinic in Los Angeles serve as a training site;

- increase AIAN cultural sensitivity by implementing an interdisciplinary curriculum in partnering with nursing, medical, and public health schools;

- increase AIAN access to specialty and tertiary care by building partnerships with county and academic facilities.

Determinants of Health Equity

- Meaningful policies adopted by institutions such as LA County, the Board of Supervisors, the new Health Agency, and other local stakeholders can lay the foundation for continued commitment to increasing the health and wellness of AIANs in Los Angeles County. Given an impending building lease expiration of the only AIAN clinic in Los Angeles, perhaps now is a good time to amass partners and resources to build a sustainable AIAN Wellness Center in Los Angeles.

Similar dedication to a vulnerable community is not unprecedented, as illustrated by the joint efforts of former Governor Pat Brown, District Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, Los Angeles County, and the University of California. Together they recognized the needs of the South LA community and committed to the cosponsoring of an Assembly bill, funding, opening, and reopening the Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital.20 On the heels of other meaningful efforts such as the Native Lives Matter and the School-to-Prison Pipeline/Restorative Justice movements, the time is ripe for considering innovations for improving Los Angeles AIAN health, wellness, and access to health care.

"Indian people still lag behind the American people as a whole in achieving and maintaining good health. I am signing this bill because of my own conviction that our first Americans should not be last in opportunity."

—Gerald R. Ford on signing the Indian Health Care Improvement Act in 1976

Acknowledgments

This brief was commissioned by the Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission and the American Indian Community Council, and was co-developed with the Los Angeles Urban Indian Roundtable.

The Los Angeles Urban Indian Roundtable members include:

American Indian Chamber of Commerce

American Indian Community Council

American Indian Healing Center

Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission

Pukúu Cultural Community Services

Red Circle Project

Southern California Indian Center

Title VII at Los Angeles Unified School District

Torres Martinez Tribal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

UCLA American Indian Studies Center

United American Indian Involvement

We would like to thank our sponsors, The California Wellness Foundation, and the County of Los Angeles Board Supervisor Don Knabe for their support of this project.

Suggested citation

Access to Care Among American Indians and Alaska Natives in Los Angeles. American Indian Studies Center at UCLA. February, 2016.

Contributions

Data analysis was completed by Jonathan Ong and Paul Ong of UCLA. Thank you to Dr. Andrea Garcia (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara) for her contributions to this brief.

Jonathan Ong graduated from UCLA with a major in Japanese and minor in film studies, and has worked as a data analyst on projects related to socioeconomic inequality.

Professor Paul Ong holds joint appointments in Asian American Studies, Luskin School of Public Affairs, and Institute of the Environmentand Sustainability.

References

Data source: United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) 3-year estimates, 2009–2011, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/pums.html.

- US Census Bureau, Population Division, “Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Race Alone or in Combination, and Hispanic Origin for the United States, States, and Counties: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014.†Release Date: June 2015. Accessed September 8, 2015, http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

- Urban Indian Health Institute, “US Census Marks Increase in Urban American Indians and Alaska Natives,†February 28, 2013.

- Donald Warne and Linda Bane Frizzell, “American Indian Health Policy: Historical Trends and Contemporary Issues,†American Journal of Public Health, vol. 104, no. S3 (June 2014): S263–S267. US Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs, “Frequently Asked Questions.†Accessed September 9, 2015, http://www.bia.gov.

- BF Seals, et al., “California American Indian and Alaska Natives Tribal Groups’ Care Access and Utilization of Care: Policy Implications,†Journal of Cancer Education 21 (Suppl., 2006): S15–S21.

- Native American Heritage Commission. “California Indian History.†Accessed September 9, 2015, http://nahc.ca.gov/resources/california-indian-history/.

- Ibid., Seals, “California American Indian.â€

- The National Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup’s Recommendations on the Indian Health Service Fiscal Year 2015 Budget, May 2013.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, “HHS FY2015 in Brief/Indian Health Service Budget Overview.†Accessed September 8, 2015, http://www.hhs.gov/about/budget/fy2015/budget-in-brief/ihs/index.html.

- Jonathan Ong and Paul Ong, “Technical Memo 2: Los Angeles AIAN Economic Indicator Brief,†UCLA American Indian Studies Center, November 2012, http://www.aisc.ucla.edu/research/pb1_memo2.aspx.

- CM Pacheco, SM Daley, T Brown, M Filippi, KA Greiner, MD, and CM Daley, “Moving Forward: Breaking the Cycle of Mistrust Between American Indians and Researchers,†American Journal of Public Health 103 (2013): 2152–2159.

- VM Mays, “The Legacy of the U.S. Public Health Service Study of Untreated Syphilis in African American Men at Tuskegee on the Affordable Care Act and Health Care Reform Fifteen Years after President Clinton’s Apology,†Ethics & Behavior vol. 22, no. 6 (2012): 411–418.

- TL Itty, FS Hodge, and F Martinez, “Shared and Unshared Barriers to Cancer Symptom Management among Urban and Rural American Indians,†The Journal of Rural Health, vol. 30, no. 2 (2014): 206–213.

- BL Cameron, P Carmargo Plazas Mdel, AS Salas, RL Bourque Bearskin, and K Hungler, “Understanding Inequalities in Access to Health Care Services for Aboriginal People: A Call for Nursing Action,†Advances in Nursing Science, vol. 37, no. 3 (2014): E1–E16.

- J. Abernathy, “American Indian Enrollment Data†(PowerPoint). Covered California for American Indians.

- California Health Benefit Exchange: Consultation with California Tribes. Accessed September 9, 2015, http://hbex.coveredca.com/tribal-consultation/.

- Indian Health Service, “Three Things You Should Know.†Accessed September 9, 2015, http://www.ihs.gov/aca/thingstoknow/.

- DL Dickerson, RA Brown, CL Johnson, K Schweigman, and EJ D’Amico, “Integrating Motivational Interviewing and Traditional Practices to Address Alcohol and Drug Use among Urban American Indian/Alaska Native Youth,†Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (July 29, 2015): ii: S0740-5472(15)00186-5.

- DL Dickerson and CL Johnson, “Design of a Behavioral Health Program for Urban American Indian/Alaska Native Youths: A Community Informed Approach,†Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, vol. 43, no. 4 (2011): 337–42.

- DL Dickerson, KL Venner, B Duran, JJ Annon, B Hale, and G Funmaker, “Drum-Assisted Recovery Therapy for Native Americans (DARTNA): Results from a Pretest and Focus Groups,†American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, vol. 21, no. 1 (2014): 35–58.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital History. Accessed Sept 10, 2015, http://www.mlkcommunityhospital.org/About-Us/Our-Story.aspx.

- Lakota People’s Law Project, “Native Lives Matter,†February 2015.

- Mike Males, “Who Are Police Killing?†Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, August 2014, http://www.cjcj.org/news/8113.

- National Congress of American Indians, “Are Native Youth Being Pushed Into Prison?†(infographic). Accessed September 14, 2015, http://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/prc-

publications/School-to-Prison_Pipeline_Infographic.pdf.